Beacon, New York, where I live now, is increasingly full of coffee shops. This small town is 90 minutes on the Metro North train from Grand Central Station, and has been growing (in population and price) thanks to a wave of young families and couples priced out of the city. This post-industrial village is shared between the laptops who bring dollars to the community, and the pickup trucks who service them. There are occasional clashes, but mostly the two populations coexist peacefully, though a little separately. On Main Street (I said it was a small town!) old Beaconites never enter the recently-opened cafes that serve latte for $4.25 to the commuter/zoom crowd. A good portion of the work-from-home denizens are in creative fields, and there’s been a growth of the gay community. Same-sex couples may be spotted holding hands on side streets, but I’ve seen them drop their partner’s hand when turning onto Main street, not wishing to run afoul of local sensibilities.

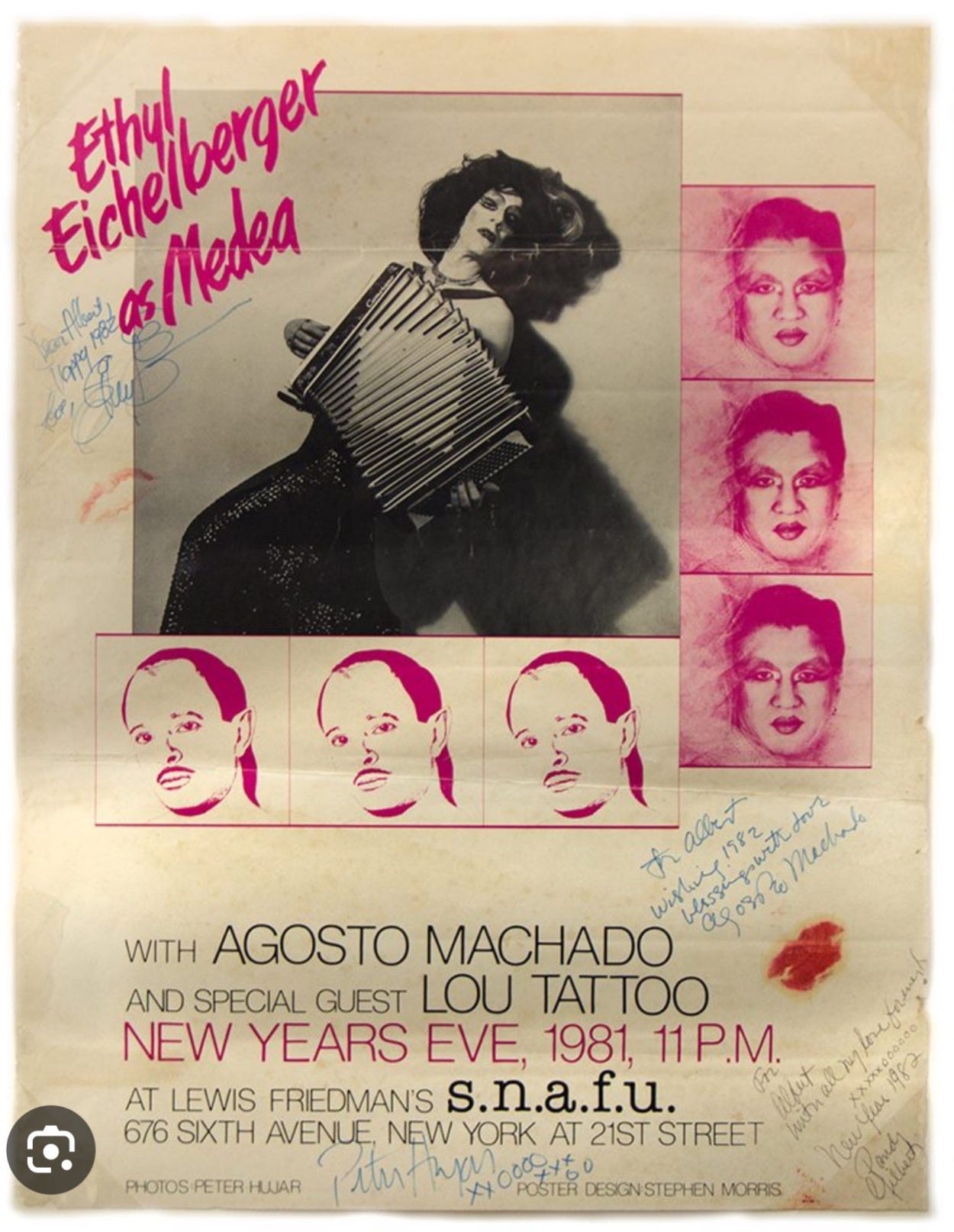

And so it was notable, recently, when a tall guy with slicked black hair, dressed in black leather boots, black leather trousers, and a black leather jacket, strolled into the Big Mouth, my local cafe, around 11:30 am. Even among the usual liberal clientele, his Village-People-like presence raised eyebrows. No one bothered him, but people noticed and exchanged glances. A few people who knew me well kept a wary eye on me: “If anyone’s going to say something to this customer, it’s going to be Bob!” But I was busy admiring his outfit, lost in a jolt of nostalgia. After he took a table in the back, I pulled up on my phone an old poster from the early 80s of a drag performer I knew called Ethyl Eichelberger. She was leaning back in a sequined dress, holding an accordion over her chest. I showed it to the barista, who was surprised (but not surprised) when I told her that leather-and-drag was my world for five years. From 1981 to 1985, I explained, I worked in Manhattan at a sometimes-raunchy Chelsea club called s.n.a.f.u. Ethyl was a regular performer there, a friend of mine, and someone I admired.

Have you noticed that people suddenly have their panties in a twist about drag queens? In the 80s it was counterculture. Then RuPaul made it mainstream. But now we’ve swung back, and in our divided culture, Governors espousing Christian values are moving to restrict or ban drag, books, and even the faintest reference to the existence of LGBTQ people. This political posture plays best to the large portion of the country that is susceptible to moral panic and/or unfamiliar with the history of theater and satire and the long cultural tradition of dressing up as the opposite gender.

Ironically, I learned a lot about Christian values in that drab, gray brick, two-story building with bars on the window and a neon sign. The name s.n.a.f.u. was taken from a military acronym that stood for “situation normal : all fucked up.” And that about sums it up. Inside those walls, “fucked-up” felt normal. More normal than normal-normal, which routinely revealed itself to be hypocritical. I wandered into s.n.a.f.u. in the spring of 1981, after meandering up sixth avenue in search of employment.

For over a month I had run into the same wall: the question on every job application, “Have you ever been convicted of a crime? If yes, explain.” As it happened, I was a felon, on probation with a suspended sentence for bank robbery — yeah, yeah, you read that right. A long story for another time soon! My robbery conviction was a mild, third-degree affair, but for some odd reason it led to some hesitation from managers in places that handle money. I’d been passed over by dozens of bars, restaurants and clubs, but it’s illegal for a felon on probation to misrepresent himself on any official document, and my probation officer would need to confirm my employment with my boss. So I couldn’t just lie.

I opened the door to s.n.a.f.u. and let my eyes adjust to the darkness. Inside was as dingy as the outside. The large room was scattered with square, gray formica tables, surrounded by black vinyl-cushioned chairs. The walls were adorned with life-sized black-and-white nude photos of couples embracing — some male/female, but mostly male/male. The photographer was Robert Mapplethorpe, now highly regarded but then controversial. A bar covered in a black oxidized tin ran the length of the place, and at the far end of the room, a small stage supported a black grand piano. As if keeping with the motif, behind the bar, a black bartender named Charlie, who handled the odd customer and signed for deliveries during these quiet afternoon hours.

I said hello and mumbled something to Charlie about looking for a job, and he led me down the bar, to a door behind the stage. Entering a short backstage hallway, I glimpsed a half-opened dressing room door with a mirrored vanity and a couple benches. Just past that, Charlie showed me into a disheveled office mostly taken up by a large metal desk covered with papers. A monthly calendar on the wall was filled in with the names of acts written in Sharpie: “the Buzzkills,” “Toads,” “Realtones,” “Holly.” A slender girl with auburn hair styled in a severe, Anna-Wintour crop sat behind the desk leafing through a rolodex. She didn’t seem to notice us.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The True Tall Tales of Bob to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.